Squishing caterpillars between one’s fingers is a tedious, time-consuming, and — at times — gooey job. But in the fields of Haiti, it’s also one that has introduced a unique way of farming, saved valuable crops, fed hundreds of families, transformed an impoverished community, and earned the trust of thousands of skeptical farmers.

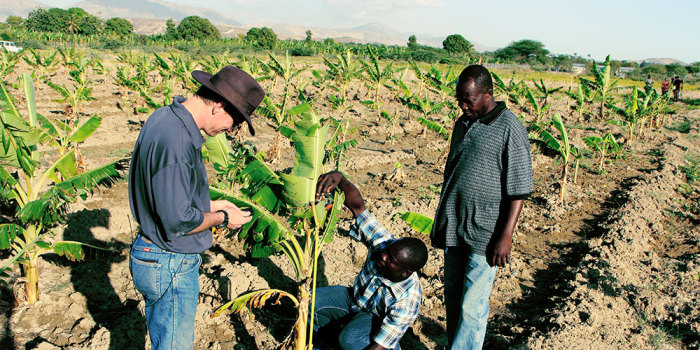

“The caterpillar problem, and more importantly how we solved the caterpillar problem, was pivotal to earning the trust of the farmers we were trying to help,” says Dr. Jason Streubel, Ph.D., who serves as Director of Agriculture for Convoy of Hope. “When the farmers saw that the answer to better crops was within their skill set, great things started to happen.”

Streubel is not overplaying the facts. In the communities where he and his team introduced the agriculture initiative, dormant fields were transformed into lush gardens and the new techniques improved the soil, which meant it was better able to withstand the weather, pests, and viruses.

“Plants became healthier, incomes rose, and most importantly children stopped going hungry,” says Streubel, noting that the initiative in Haiti is just over two years old. “Across the board, the initiative has helped improve everyone’s health, sense of pride, and their bottom lines.”

On a sweltering day in Turpin, Haiti — one of the first communities to embrace the Agriculture initiative — Streubel makes his way down a sliver of a trail on a lush hillside. After rounding a grove of trees, he stands on the edge of a massive valley. In all directions, fields are brimming with corn, maize, okra, sorghum, black beans, and pigeon peas.

“It wasn’t like this four months ago,” he says, surveying the landscape with a scientist’s eye. “This is good to see; the valley is filled with food and hope.”

Pastor Ellison, a local leader who was instrumental in rallying farmers to embrace the Agriculture initiative, concurs.

“Before the project started this valley was empty,” he says. “But now all you see is crops in every direction. Our people are very happy and proud of this!”

Farmers in the Agriculture initiative receive education, training, tools, and virus-resistant seeds. In exchange, they give 10% of their harvest to Convoy of Hope’s Children’s Feeding initiative.

“Convoy of Hope has been strategic in building programs that not only meet immediate needs, but also provide long-lasting solutions that will improve people’s lives and give them hope for years to come,” says Kevin Rose, Senior Director of International Program Operations.

Streubel agrees. “When the poorest of the poor are equipped with the tools and education to improve their lives, the possibilities are endless.”

Anio, whose children are enrolled in a local school where they receive a nutritious meal each school day from Convoy of Hope, is dreaming big dreams.

‘Before the project started this valley was empty. But now all you see is crops in every direction. Our people are very happy and proud of this!’

—Pastor Ellison, Haiti

“I want my children to be doctors or engineers or agronomists,” she says, as she spots a caterpillar. “This program has blessed our family and the children of this community.”

Less than two miles from Anio’s field is a gathering of newly-recruited farmers. They sit on roughly hewn benches in a tiny church. An agronomist working for Convoy of Hope and its in-country partner, Mission of Hope, explains how agricultural conservation [farming without pesticides and fertilizers, keeping farming costs low and protecting environmental and human health, according to Streubel] is not only possible, but will increase yields. Most of the farmers nod in agreement, but there are a few who are not convinced.

Streubel isn’t surprised by the skepticism. After all, everything the farmers are learning today runs counter to the way generations of their families have farmed.

“Two years ago, when we told the farmers they were going to have to hand-pick every caterpillar off their plants, most of them scoffed at the idea,” says Streubel. “But when the fields flourished where the caterpillars were taken off the plants and the fields around them were decimated, we earned a lot of trust.”

Back in Springfield, Missouri, at a local university where he also serves as an associate professor, Streubel sits in his third floor office. His shelves are lined with books covering topics such as chemistry, microbiology, plant propagation, agriculture, genetics, and botany.

At the moment, he’s far removed from the fields where he is usually found mucking in Wrangler jeans and steel-toed, three-quarter-shank work boots, peering at the earth and its harvest under the brim of the Indiana Jones hat he bought at Disneyland.

“What’s happened in Haiti through our Agriculture initiative will eventually be replicated by Convoy of Hope in countries throughout the world,” he says. “By introducing a new way of farming we are seeing the foundation for long-term transformational change laid. It’s exciting to know that we get to play a part in solving real-world problems while also instilling a hope for the future in this generation, and in generations to come.”